Volumes 1,2, and 3 now available in paperback [go to Amazon]

A NOVEL OF PLUNDERED RETIREMENT ACCOUNTS, INTERNET-ENABLED SUPERPOSITION, AND GERONTICIDE.

INTRODUCTION

March, 2020:

Geronticide, the central theme of this trilogy, has no formalized policy basis. History reveals, however, that societal extremes can blossom when need, means, and justification coexist and provide fertile ground. This novel is a dramatization of these factors coming into alignment, thereby making geronticide an acceptable (indeed, accepted) governmental function. To Be, and Not To Be is of the future but not fantasy.

That the democratic ideal can be compromised is more than possible. It's a clear and present danger. Targeted misdirection and the manipulation of apathy as well as native passion – the intertwined banes of democracy – can weaken it from within. Personal minutia – surreptitiously extracted, analyzed, and cataloged to facilitate directed mercantile sops and the short lasting sugar-highs of small social satisfactions – can be the tools of malignant mercantilism. Ephemeral trivia – tailored to amuse and to arouse – can placate and diminish the inclination for as well as the relevance of serious thought.

Fear can be orchestrated, even manufactured, to serve political agendas.

In 1959 Aldous Huxley offered the prediction that "... there will be within the next generation or so a pharmacological method of making people love their servitude, and producing ... a kind of painless concentration camp for entire societies, so that people will in fact have their liberties taken away from them but will rather enjoy it, because they will be distracted from any desire to rebel ..." This laborious passage has turned out to be essentially correct, except that it took more than a generation and the facilitating agent has not been a drug but the Internet. And how much more convenient, pervasive, and manageable this has proven to be.

It's fair to say that we, as a nation, have become complacent with regard to trading away our individualities and freedoms for false promises. We have allowed ourselves to be inured to those aggregators on social and media platforms who profess to champion choice and openness but whose aim is the very opposite. While our nation has survived physical and financial trauma with its democratic character intact, whether it can withstand coincident internal attacks upon its fundamental, its founding principles is open to the serious questions dramatized in the To Be, and Not To Be

trilogy.

We're accustomed to thinking of history as fixed, its record of events diverse and dispersed. Formerly it took much effort to make a coherent and consistent story of the whole of it. But now, with centralized information management, reconfiguring the past, even the present, to justify a singular, desired future has become a matter of editing not rewriting, a matter of minutes not years. To Be, and Not To Be is an exploration of how this changes the lives of its characters, as it could ours.

Shoshana Zuboff's recently published ( 2019) sociological study, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism - The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, is an academic parallel to the fictional setting of this novel. Her detailed analysis validates the veracity and relevance of its theme. Fictional portrayals as well as formal discussion most often stem from critical observation of which we all can partake. They are the result not the cause of significant societal trends, the recognition of which may show considerable latency.

Neither geronticide, as stated above, nor euthanasia are current official policies. How these might be institutionaled is a theme of this novel. Another is purposeful, directed, and inescapable oversight, which is itself not a frankly fictional construction. It's an aspect of virtually every segment of our lives – recreational, vocational, social, financial, medical. This, however, is merely a continuation of trends firmly in place, trends of which we'd long ago been warned. In addition, the mutually reinforcing combination of computerization, media, and the World Wide Web has made us hungrier for fast facts, indeed for solemn truths, than ever before. Unfortunately, the technology is arcane, news and commentary are corporate and agenda driven, and the Internet is primarily mercantile. Within that complex reality, facts are labile, candor undervalued, and incontrovertible truths rare. Sadly, many still refuse to accept this assessment. Most believe they can "know." Yet, to greedily absorb specious apprisals and think one is therefore informed is worse than being ignorant. It opens the door to manipulation and control. This is what we need to fear in the years to come.

Corrosive extremism is on the rise. Politicized theology is distorting governance, much as in the Mideast. Covert forces are molding the media, indeed facts themselves, as we see exemplified virtually daily. In the background, the public sector has commitments it can't afford and the private sector has gained dominance it can't justify. This potent brew has been made palatable as well as possible by general prosperity. But what if that prosperity were to fade? The world witnessed the result in Europe when similar factors were aligned. What would be the result here were we, in this century, to suffer a malignant financial crisis, one which, once again, would provide ample justifications for forceful action? Who would suffer? Who would become the designated victims?

This is a long story, made all the more frightening by recent trends. Its fictional depiction of a plausible future, its photographs and graphical insertions, are intended to resonate with our own real, present lives. As the novel opens, Barnard Cordner, retired academic economist, is confronting more than aging. He has reasons for suspicion, personal as well as practical. Financial markets are in serious decline, as is America's global stature. The loss of his retirement funds was unavoidable, even predictable. With U.S. sovereign debt suspect and the federal government faced with an urgent need to trim entitlements, the transfer of seniors to attractive but remotely located Elder Edens is underway. Relocation, as this newly implemented policy is called, is designed to put to better use the retirement assets they had set aside. Barnard fully understands the country's economic realities and isn't surprised by the dramatic ascendance of the far right, theocratic political ideology that has envisioned Relocation. Nonetheless, he resists the call for urban seniors to relocate to rural retirement communities. These may not be what they seem. Barnard and his close companion, Sallie Bass, must contend with a present that isn't what they had planned and saved for. Moreover, they face a future that is, at best, ambiguous. He, they will ultimately learn of the difference between remaining real and simply remaining.

To Be, and Not To Be, a fiction that has become dishearteningly current, attempts to explore a labile reality and what it means to struggle within it. The major stock market crash of early 2020 may have set in motion exactly the economic sequence that will make the fictional theme of this novel a reality, a fiscal necessity.

A BRIEF GUIDE

To Be, and Not To Be is serious fiction, much of it extrapolation when privately printed (2013) but already palpable by the time of the first trade edition (2016). Parts of this work are deliberately obscure, other inadvertently so. The former I can address.

That one can be misled as to what is historically accurate, even with respect to one's own life events, is as much the style of the story as it is the story itself. The introductory chapter uses the puzzled protagonist's viewing of a familiar old film to set that tone. The intent is to have the reader share, not merely be informed of, Barnard's uncertainty. That several early readers recommended that I see Casablanca again, so as to correct my apparent plot errors, was heartwarming.

The theme, the dramatic framework: ... is dispensing with the old, the few, in favor of sustaining the many. Made plausible by ongoing events – political as well as societal, international as well as domestic – the content and projections of the novel are chilling, especially so since, as envisioned, the fictional tale is meant to be credible, if not always factual.

The first issue, therefore, was: How could the social landscape, within which the story would evolve, become so harsh as to yield the events described? Could that derive from a climatic misfortune or an extraterrestrially ordained catastrophe, as in the fertile field of science fiction? Could it be the consequence of political upheaval? History does provide many instructive examples of political movements producing profound social change. But these merely displace the issue, do not provide a useful proximate cause, viz, the impetus for that precipitating crisis.

Academic formalisms are not needed to posit that most, if not all, social-political turning points hinge upon basic economic issues – having less than one, or a class, or a country needs or wants. Extreme economic disarray, therefore, was adopted as the origin of the dysfunction that is the armature of the novel. The widespread anxiety accompanying the previous decade's financial collapse provided a more than sufficient model, as did the 1920's and 30's. Indeed, many pundits had, near the end of this millennium's first decade, voiced their fear of a doomsday scenario for the world's financial system. The US and the world economy did recover. But what if they had not? Were an even more dire panic to come again, in which direction would the popular will turn?

History, again, is the place to look for hints of a possible future. What it reveals is that anxiety is often used by a few to foster extreme reaction from the many, a reaction that is usually less than thoughtful, less than generous, and virtually always a departure from the prior prevailing ethic. Is this not exactly what we are experiencing as these notes are being written?

The title: ... as should be obvious, refers to (mocks, perhaps?) Hamlet's terse query. While not meant as an elaboration of the fictional character's well known soliloquy, the novel does offer a parallel to its philosophical substance. Indeed, one of the chapters carries the title " ... AND NOT TO BE." Here, however, the unsolvable puzzle is made analogous (loosely, of course, since the protagonist is insufficiently expert) to the paradoxes of quantum mechanics.

The book's subtitle ("The Rise of Misplaced Power ...") comes from President Eisenhower's farewell address to Congress. On that day, well over a half century ago, he was facing an audience of legislators, but, without doubt, his warning was meant for all to hear and consider. We are now clearly immersed in a world of "misplaced power" – in the media, in bureaucracy, in hyper-funded special interest groups, in corporate and financial consolidation, in the Internet – much of which we have delegated and abetted. We have been too willing to ignore the degree to which this delegation could be fundamentally deleterious despite superficial benefit. Prognostications are often faulty. Yet, as expressed by Dickens' Scrooge, "Men's courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead."

Some will note that the novel is harsh on the young, is a tedious polemic perhaps. They are not being blamed, however. It is simply that it is for them and by them that serious redirection of the course of our lives takes place. The older generation, wise as it may be, is too conditioned by habit and established personal circumstance to embrace change as does the younger. Could the latter be a harbinger of the decline of democracy not by force but by disinterest and misdirection? It is my hope that the subtext of this novel is merely a reflection of the potential for the elaboration of a form of tyranny by default, that the whole of it is only a frightening entertainment far from present reality, one much like an extraterrestrial invasion adventure film. However, neither is a new nor inconceivable concern. In the sound track (1984!) to Metropolis, Music by Giorgio Moroder, Lyrics by Pete Bellotte, we have already heard:

How do we see clear?

Answers can change the question line

Every time

And now the truth in confidence

Tells a lie ...

What's going on? I wanna know

That's from over thirty years ago, but it fits the current (Trump) administration better than OJ's glove!

Anomie: To Be, and Not To Be was conceived with no overt philosophical agenda. However, while immersed in the task of crafting that fiction, I became increasingly sensitized to the realities of current trends. After typing "The End" and beginning the serious literary editing that any decent novel deserves, I realized that the work had evolved into an exploration of the anomie that is increasingly detected in the media and in the mores of society at large. That term, anomie, refers to a readjustment, perhaps even a breakdown of established social norms, a "moral deregulation" if you will, accompanied by "alienation and purposelessness" (Wikipedia), and a diminution of the integrity of the self.

This increasingly evident anomie is, however, more than a subgroup's incidental trend brought on, as in Durkheim's view, by the shift to a mechanized, industrial, or, in our context, a computerized society. In its current form, it is the unintended(?) consequence of a designed, post-industrial transition to focused consumerism, with fake, diligently inserted needs thereafter satisfied by fake, ephemeral rewards (e.g., six month new product cycles. Or Pokemon GO!?!).

Why in six parts: Experience comprises sequential action. At every moment many options are possible, but, as individuals, a single path will be taken, a unique future instantiated. The simplest creatures have only external physical stimuli and their own structural attributes to make the difference between success or failure, living on or dying. We, at the opposite pole of evolution, are more richly endowed. However, thoughtful action may be compromised by chance or overridden by reflex; social norms may be disregarded in favor of instinct or fear.

Our paths, therefore, are rife with confliction. Categorizing the basis or cause of an act is not an easy task. Aiming more for literary symmetry than philosophical precision, the novel is arranged around six distinguishable attributes: innate, instrumental, accidental, idealistic, reflexive, or institutional. Yes, these may not be fully separable. A more meticulous analysis of the nature and identification of choice is for others to attempt. It is sufficient for the narrative that the etiologic hexad is intuitive and illustrative.

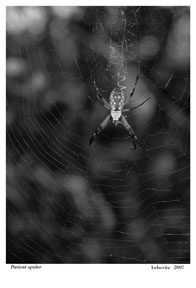

What Barnard Cordner – former physics student, one time Naval officer, retired academic economist – would like to believe is that it is a deterministic (hence, predictable and controllable) world. Presuming that there is always some preceding cause, some reason to consider if not to assign, provides a secularist with a measure of security. This is Barnard's history. He would prefer that what he does, he does for a discernable reason. In each of the novel's sections – using the device of spiders and their webs (the latter like the nexus that is the Internet, perhaps?) – he observes and considers in turn one of the above six (loosely distinguished) aspects of "Why?" Likewise, each major character's motivation, while not monadic – again, in submission to the needs of narrative flow – is similarly constrained.

Introspective to a fault, Barnard must contend with choice having a multiplicity of dimensions, with primacy often undecidable. That there are many ways to assign causality, with none of them definitive, may mean that the attempt to do so is inherently futile. Worse, by the end of the novel, he comes to feel that the effort to understand has become irrelevant, that to know Why no longer has significance. He is faced with an indeterminacy as conceptually unresolvable as are the contradictions inherent to the quantum physical principles that he had found so disorienting as an undergraduate and had wanted so desperately to be able to grasp.

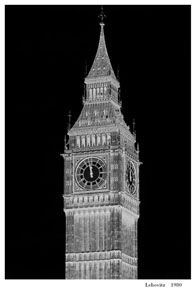

The photographs: ... are (with one exception) the work of the author. Each illustrates a salient point of each of the novel's six sections. The frontispiece photo of London's Big Ben, taken over a third of a century ago without conscious premeditation, just happened to show two minutes to twelve, or to midnight as I chose to put it by reversing the B/W image for the novel. Its insertion implicitly references the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and is meant to reinforce the novel's theme of the danger of an apocalyptic social reordering. As it happens, in January of this year (2018), in response to world events, the Bulletin shafted their assessment to precisely that setting.

In sum: The novel toys with the appreciation of reality and what may lie behind any administrative alteration of it. Although not fully factual, the story is plausible, increasingly so with every news report. The current chapters 1, 13, 18, and 32, for example, while edited (as has been the entire novel) for style and clarity, are essentially unchanged from the corresponding content in the private printing of 2013 yet read now as if they are, respectively, puzzled, angry, besotted, cynical commentaries on current events.

Hopefully, the protagonist's uneasy present will never become our own.

Camus is now passé. Few would claim to be existentialist in that fashion. Yet, there is a great deal of similarity between what he set down (in The Stranger, for example) and what this novel attempts to dramatize. "Live for the moment" is no longer simply a hippie's slogan, an expression of ennui. It has become commonplace, neither erotic nor remarkable. From the polar opposites of existentialism's self-focus and industrial capitalism's acquisitiveness has come the synthesis of a new social imperative – consumption for its own sake. What exists for many – and what will become progressively more acute with the onset of awareness – is the mismatch between what is implicitly promised and what can be explicitly attained. Wide spread, deeply rooted anomie is the inevitable result of this economic dialectic. Where this may actually take us is difficult to ascertain. We do know, however, where it has led in the past.

Or do we?

Better put, in view of the trend, is: Will we be able to?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert M. Lebovitz, Ph.D., resides in Dallas, Texas. With graduate degrees from Cal Tech and UCLA, his early professional positions were as an aerospace industry engineer (Hughes Corp) and consultant (RAND Corp). His three decade, postdoctoral academic career, in neurobiology at the University of Texas Health Science Center Dallas, covered a wide range of interests derived from his background in applied physics and biology. His work was supported by peer reviewed grants from NIH, NIEHS, ONR, and others. He has published in the areas of the neurobiology of the epilepsies, the biological effects of low level electromagnetic radiation (endocrine, reproductive, sensory, behavioral), and theoretical (computational) neurobiology. Having a long standing interest in writing literary fiction, he had made use of limited free time to compose a few published humorous pieces and unpublished short stories. With retirement (1998) came the opportunity to more fully develop this interest. His first work of substantial, deliberate fiction, the lengthy novel To Be, appeared in 2013. It is a dramatization of the rise of recidivist nationalism and the resulting consequences for seniors after a period of extreme national financial panic. In 2018 his compact fictional tale of a couple's journey into Alzheimer's Disease (We Never Do Wednesday's) appeared as an Amazon paperback book. With so many of its anticipations having been realized, this major revision and factual update of his debut novel became available in paperback in the same year, as the To Be, and Not To Be trilogy.